|

Interdisciplinary

Journal on Human Development, Culture and Education

Revista Interdisciplinar de Desenvolvimento Humano, Cultura e Educação

ISSN: 1533-6476 |

| Tikunakids

/ Crianças Tikuna

Aldeia Filadelfia BenjaminConstant, Amazonas, Brasil photo (c) Marcelo Lima Editorial

policy /

Review

Essays /

Notas

de Leitura

Books

received /

general

index

Sign

our /

Leia

o nosso /

READER'S

FORUM

|

VOLUME 1 Number 3,

June, 2002

What Is Psychology of Liberation?

It is Cultural Psychology

Abstract This paper argues that a psychology of liberation must be cultural psychology. Psychology of liberation promotes humanitarian social change. It does so by identifying and critiquing destructive cultural influences which foster debilitating psychological phenomena, and it identifies and supports benevolent cultural influences which foster fulfilling psychological phenomena. Cultural psychology is the best approach for accomplishing these analyses. Cultural psychology regards psychological phenomena as originating in and reflecting cultural factors and processes. It therefore identifies benevolent and destructive cultural influences on psychology. This paper explains the principles of cultural psychology. It utilizes Vygotsky’s activity theory as a conceptual basis for cultural psychology. And it presents contemporary empirical evidence to support these principles and concepts. In developing a psychology of liberation,

the key question is, "what do we mean by liberation?" The way we define

liberation determines the kind of psychology of liberation that we develop.

If we believe that liberation consists of expressing oneself, the

psychology of liberation would investigate psychological processes that

promote this. If we believe that liberation consists in forming personal

meanings about things, then a psychology of liberation would consist

Most of us at this congress believe that liberation must be defined more culturally. It must include transforming the culture in which people live — humanizing social institutions, practices, conditions, and values. Such cultural change is imperative for real liberation. Accepting oppressive social conditions diminishes human liberation. How can psychologists contribute to cultural analysis and change? We can do so by studying the effects of cultural factors and processes on psychology. This approach will identify fulfilling psychological functions and trace them to positive cultural influences. It will also identify unfulfilling, debasing, anti-social psychological phenomena — e.g., insecurity, anxiety, irrationality, prejudice, self-destructive behavior, selfishness, and aggression — and trace them back to negative cultural influences. Identifying positive and negative cultural influences on psychology will point out the ones which need to be promoted and the ones which need to be transformed. In this way, psychologists can contribute to the liberation of people. This is precisely the kind of analysis that Martin-Baro made of fatalism among Central American peasants. He traced fatalism to real social relations and conditions of the peasants. He argued that these must be changed in order to free people of fatalism. Martin-Baro engaged in a cultural analysis of fatalism. His psychology of liberation was clearly a cultural psychology. It contrasts with conventional psychological analyses that attribute fatalism to personal processes. By disregarding cultural relations, psychologists fail to analyze and improve them. If psychology of liberation is cultural psychology, we must develop the field of cultural psychology in order to help people liberate themselves. I have been working for several decades to develop a theoretical and methodological framework for cultural psychology. I will outline some of the main ideas. Cultural psychology is first and

foremost a scientific discipline. It studies culture as it is embedded

in, and refracted in, individuals’ psychology. This supplements the perspective

of political science and sociology which study culture directly, as a system

of behavioral norms and policies. Cultural psychology employs particular

theories and scientific methods which are appropriate to elucidating psychological

effects of cultural factors and processes. Cultural psychology is a check

on political analyses. It may confirm or disconfirm them. Without independent

scientific information about the effects of culture on people, political

analyses are subject to self-confirming, erroneous thinking.

In my opinion, the best conceptual foundation for cultural psychology is the work of Lev Vygotsky. Vygotsky was a Marxist. He sought to develop a cultural psychology that was both scientifically rigorous and also useful for progressive social change. Vygotsky developed a sophisticated model of psychology. He gained great insight from Marx, but he built on Marx’s ideas rather than mechanically applying them to psychology. Vygotsky enumerated three cultural factors which organize psychology: 1) Activities such as producing goods, raising children, educating the populace, devising and implementing laws, treating disease, playing, and producing art. 2) Artifacts including tools, books, paper, pottery, weapons, eating utensils, clocks, clothing, buildings, furniture, toys, and technology. 3) Concepts about things and people. For example, the succession of forms that the concept of person has taken in the life of men in different societies varies with their system of law, religion, customs, social structures, and mentality. These three factors

interact in complex, dynamic ways with each other and with psychological

phenomena. The system of cultural activities, artifacts, concepts, and

psychological phenomena is culture. Vygotsky emphasized that social activities

exert more influence on the system than the other factors do. The reason

is that humans survive and realize themselves through socially organized

activities. In order to eat, a number of people have to organize together

in a coordinated pattern of behavior to gather, hunt, or produce the food.

In addition, they must socially coordinate ancillary

Vygotsky explained

the formative influence of activities on psychology in the following words:

"the structures of higher mental functions represent a cast of collective

social relations between people. These [mental] structures are nothing

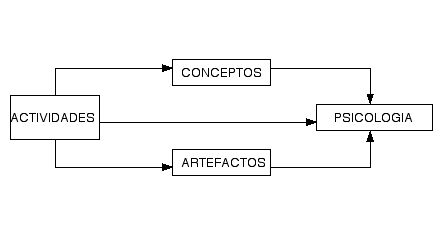

Vygotsky’s activity theory can be roughly diagrammed in figure 1:

Figure one emphasizes psychology’s dependence on the other cultural factors and the dominance of activities over all the factors. The real situation is more complex and dynamic. It contains reciprocal influences among the factors. And it is animated by intentionality, teleology, or agency. Vygotsky (1997a, p. 206) emphasized that "Man’s relationship to his surroundings must always bear the character of purposefulness, of activity, and not simple dependence." I don’t have time to discuss the full complexity of activity theory. (I do so in my recent book, Cultural Psychology: Theory & Method.) I shall only deal with a small portion of the model here. I’d like to present evidence that illustrates the impact of cultural activities and concepts on psychology. We can then discuss how this cultural psychological research contributes to liberation psychology. A fascinating

historical study by Cressy (1983) shows that reading is inspired by socially

organized activity. Historical evidence from the sixteenth through the

eighteenth centuries reveals that "literacy was…an appropriate tool for

a particular range of activities" (p. 37). The most important social activities

for inspiring reading were economic ones:

In France, for example, the north and east were more accomplished than the south and west. The far north of England was more illiterate than the area around London, while the English settlers of Massachusetts Bay were much more fluent with reading and writing than their contemporaries in the outlying parts of New England or in the southern colonies. Cultural and ideological pressures were certainly influential, but the factor which ties together these pathfinder regions for literacy was their level of economic development. Their overall environment was more demanding of literacy. This is even more clear at the local level. Farming communities were less literate than trading communities, while within the world of agriculture there were cultural, educational, and economic differences between commercial grain growers and family subsistence farms, between suppliers of meat for the urban market and upland or marshland shepherds (p. 35). The activity basis of reading for different occupational groups was as follows: As the complexity of one’s dealings increased, so did the advantage of being able to decipher writing and record things on paper. The farmer who could jot down market prices and compare them from week to week or season to season could secure a commercial advantage over his illiterate neighbor who relied on his memory…Reading and writing would become useful and thereby worth knowing (p 29). Cressy notes that educational efforts to promote literacy were only effective when there was practical economic need for the skill. For people who had no practical economic need for literacy, "however persuasive the rhetoric, it foundered on the indifference to literacy of the bulk of the population who saw no practical need for those abilities. Where people needed little literacy to manage their affairs…it was difficult to persuade them to embrace a skill which was, for all practical purposes, superfluous" (p. 40). Fascinating research has demonstrated that cultural concepts also shape psychological functions. Concepts act as filters which mediate perception, emotions, memory, self-concept, body-image, and mental illness. Smith-Rosenberg (1972) explained 19th century hysteria as resting upon cultural concepts. Hysteria was prevalent among white, upper middle class women in the U.S. and Europe. It was rare among men and among lower class women. Hysterical symptoms included deadening of the senses and immobilizing the limbs. According to Smith-Rosenberg, these symptoms reflected the middle class feminine ideal of a weak, spiritual, person. Normal middle class women were expected to shun physical work, take no interest in bodily pleasure, and avoid the mere mention of bodily functions. Even the breast of chicken was euphemistically called white meat to avoid reference to anatomical parts. The ideal Victorian young women was very slim and weak. Her body was restricted by eating extremely little and by wearing tightly laced corsets that produced an 18 inch waist. Normal Victorian middle class women cultivated physical debilitation in order to realize the ideal of weakness, delicacy, gentleness, purity, submissiveness, and freedom from physical labor. The debilitating symptoms of hysteria were only a slight exaggeration of middle class feminine ideals. Middle class hysteria was sympathetically accepted by men and women as characteristic of women. When some working

class women adopted hysterical symptoms, they were perceived much more

critically. They were assigned occupational therapy to motivate their return

to gainful employment. Middle class women, in contrast, were

Hysteria was only common during a century from the end of the 18th century to the beginning of the 20th. After the First World War these motor disturbances vanish as swiftly and mysteriously as they arose (Shorter, 1986).With the contemporary feminine ideal being different from last century, hysterical symptoms embodying that ideal are rarely encountered. Only 0.27% of inpatient and outpatient female admissions to North American psychiatric hospitals were diagnosed in 1975 as manifesting conversion hysteria. (Winstead, 1984, table 1). The Liberating Potential of Cultural Psychology Identifying the

cultural activities and concepts that mediate reading and mental illness

has important uses for human liberation. Enhancing positive psychological

capabilities such as reading requires promoting the cultural activities

and concepts that foster them. Positive psychological capabilities are

not free-floating phenomena that can be readily acquired independently

of cultural factors. Conversely, meliorating debilitating psychological

phenomena such as mental illness requires eliminating the cultural factors

that foster them. Debilitating psychological phenomena cannot be

Action can be taken on a personal and a societal level. Individual hysterical women could be treated in therapy by examining the cultural ideals that they have internalized. It would be necessary to understand and reject these ideals if hysterical symptoms are to be relieved. Discussing purely personal issues with the patients would overlook the cultural concepts that organize the symptoms. The cultural ideals of passive femininity must also be challenged on a societal level. Broad educational campaigns would need to question this ideal throughout society. Reducing its prevalence would limit its salience as an image for women to adopt in coping with their difficulties. As long as it remained a prevalent ideal, large numbers of women would adopt it as a means for coping with problems. Activity theory further emphasizes that challenging cultural concepts requires corresponding changes in the social activities of people. For, concepts are based on real social activities. The cultural ideal of a passive, weak woman was based on women’s subservient social position. The ideal will only be abandoned if the role of women is altered. Cultural psychology

has an additional importance for liberation. By identifying cultural activities

and concepts embedded in psychological phenomena, it reveals whether the

latter recapitulate existing cultural factors or whether they point toward

new ones. Activity theory distinguishes genuinely novel behavior (which

surpasses prevailing cultural activities and enhances the fulfillment of

people) from acts which are superficial variations of the status quo. For

example, many women who adopt the personality trait of assertiveness believe

they are liberated because they are realizing their

true selves. However, activity theory reveals that this change in women’s

personality was induced by economic pressures to join the labor force.

With real wages of U.S. men declining from the 1970’s until today, a family

could only maintain its standard of living if women entered the labor force.

Under this economic pressures, women participated in the bourgeois economy

with its competitiveness, materialism, depersonalization, alienation, and

individualism. A cultural psychological analysis might reveal that these

characteristics permeate women’s assertiveness

People often underestimate

the extent to which their psychological phenomena embody cultural activities

and concepts. Consequently most people believe that they have transcended

their culture when they have not. Cultural psychology is

the only psychological theory that can analyze the extent to which psychology

recapitulates existing cultural factors and the extent to which it draws

on alternative cultural factors. Therefore, cultural psychology is the

only psychological

References

Cressy, D. (1983). The environment for literacy: Accomplishment and context in seventeenth-century England and New England. In D. Resnick (Ed.), Literacy in historical perspective (pp. 23-42). Washington: Library of Congress. Malinowski, B. (1944). A scientific theory of culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. Ratner, C. (1991). Vygotsky's sociohistorical psychology and its contemporary applications. N.Y.: Plenum. Ratner, C. (1997). Cultural psychology and qualitative methodology: Theoretical and empirical considerations. N.Y.: Plenum. Ratner, C. (1998). The historical and contemporary significance of Vygotsky's sociohistorical psychology. In R. Rieber & K. Salzinger (Eds.), Psychology: Theoretical-historical perspectives (pp. 455-474). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. Ratner, C. (1999). Three approaches to cultural psychology: A critique. Cultural Dynamics, 11, 7-31. Ratner, C. (2000a). Outline of a coherent, comprehensive concept of culture. Cross-Culural Psychology Bulletin, 34, #1 & 2, 5-11. Ratner, C. (2000b). A cultural-psychological analysis of emotions. Culture and Psychology, 6, 5-39. Ratner, C. (2002). Cultural psychology: Theory and method. New York: Plenum. Risman, B. (1987). Intimate relationships from a microstrutural perspective: Men who mother. Gender and Society, 1, 6-32. Shorter, E. Paralysis: The Rise and Fall of A `Hysterical' Symptom (1986). Journal of Social History,19, 549-582. Smith-Rosenberg, C (1972). The Hysterical Woman: Sex Roles and Role Conflict in 19th Century America, Social Research, 39, 652-678. Vygotsky, L. S. (1997a). Educational psychology. Boca Raton, Florida: St. Lucie Press. (Originally written 1921) Vygotsky, L. S. (1997b). Collected works (volume 3). New York: Plenum. Vygotsky, L. S. (1998). Collected works (vol. 5). New York: Plenum. Winstead, B (1984). Hysteria. In

C. Widom (Ed.), Sex Roles and Psychopathology (chap. 4). New York: Plenum.

copyright

(c) 2002 Centro de Estudos e Pesquisas Armando de Oliveira

Souza CEPAOS

endereço

phone

+ fax: (55) 11 - 50837182 Brasil

|